- Home

- Clayton Emery

Star of Cursrah Page 19

Star of Cursrah Read online

Page 19

Atop the hill, Amenstar could see half the horizon to the south and east. As Gheqet had noted, the chuckling river ran in its own ancient trough, and a stone ridge a quarter-mile thick separated the precious water from Pallaton’s erratic dirt ditch running north. Amenstar was trying to think of something clever and defiant to say when the prince spoke.

“Remember the legend of Ajhuutal? It was a prosperous seaport east of Coramshan.”

“I remember,” replied Star, vaguely. “It sank into the sea and became the Spider Swamp?”

“That’s it. It was long ago, when Calim still strove to conquer this land. He wrestled with a marid named Ajhuu in the Steam Clashes. Finally Calim unleashed an earthquake that shattered thirty miles of the River of Ice into a crumbly delta. The sea rushed in and created Spider Swamp. Coramshan calls the event the Shattering. I suppose now it’s safe to use the old name, the Ajhuutal Mutiny.”

“It’s never prudent to mock Great Calim.” Star deliberately raised her voice so the sky might hear. Still, her breath came short from a tight chest, as if disaster portended. “Will you unleash magicks to undo the enchantments of our benefactor? Only lesser genies ever gave Great Calim a battle.”

“I can ply the greatest of magicks … Calim’s own.” Pallaton’s teeth glowed like wolf fangs as he scanned the sky. Reaching a decision, he called, “Trumpeter, blow!”

With a flourish, the military engineer saluted, puffed his cheeks, and blew a long horn blast. Instantly, like an anthill kicked open, slaves spilled from the dark ditch and streamed up the rocky slopes. When the brown-and-white bodies were halfway up, the prince nodded to the chief vizar.

“If it please your grace,” said Pallaton, “you may commence.”

The vizar in red raised the curved staff over his head and loosed a wail in some arcane language that made Star’s skin crawl. Five more vizars, standing at five points around their chief, added more wails like men enduring torture. Gheqet and Tafir glanced about wide-eyed, as did soldiers guarding the perimeter and the samir’s bodyguards.

Pallaton swayed from foot to foot, excited as a child, and said, “That staff is said to be Calim’s Scepter. It should be—we paid a fortune to grave robbers for it!”

Amenstar sniffed. “At Cursrah’s College we have warehouses stuffed with mystical gimcracks,” she said. “Most are fakes.”

“As may be,” Pallaton conceded, “but our wisest vizars think this curved stick is genuine. We’ll find out now if it is.”

The chanting dragged on until Amenstar wished to cover her ears. Junior vizars burned incense and threw offerings of rice and cinnamon to the four winds. Nothing seemed to happen, until Pallaton pointed upward. The sun had been occluded by a high haze. Gradually the haze lowered and thickened, becoming a full overcast that darkened the land. A stiffening breeze made Star shiver. Far away on the slopes, slaves raised brown arms and murmured in awe.

The chief vizar’s weird wail reached a crescendo. Howling, the man raised the staff high and stabbed it hard upon the hilltop toward the river, so hard Amenstar wondered the shaft didn’t shatter.

A rumble shook the world, and people glanced up.

Tafir muttered, “That wasn’t thunder.…”

A tremor trilled through their legs.

“Wh-what—” bleated Amenstar. “L-lords of L-light-t-t-t.…”

“E-er-earthquake,” chattered Gheqet.

Another rumble rolled past, a grumbling toll like a monstrous iron bell. On the slopes above the new ditch, rocks trickled from peaks, and slaves scampered to avoid small avalanches. A hollow boom sounded. Amenstar squeaked and fell to her knees. She’d seen the hills move.

Along the banks of the Agis, a stone ridge flexed as if Great Calim had snapped a blanket. A rising, rippling boom slowly cracked hills further along the river’s northern side—where the vizar had aimed in striking the staff. A soldier shouted above the roar. Everyone pointed and screamed together.

The north bank of the River Agis—solid stone—dissolved.

As if tired, rocky ridges forty feet high suddenly let go and slid into the riverbed. Untold tons of stone dropped into thousands of gallons of water. Displaced, water gushed into the sky as if a child had stamped in a puddle. In slow motion, the water arched high above, then rained and spattered torrents over broken ridges. Another cascade shot higher than the hills, pounded the landscape, and dislodged more rocks.

The spectators felt another temblor tingle their toes as the earth bucked like a wild horse. Another slab of hills, a newly uncovered face, broke free and followed its brother to crash into the riverbed. More water squirted—a murky brown deluge. Thrown off her feet, Amenstar sprawled facedown, hands and knees scuffed raw. The vizar, his acolytes, and soldiers also clutched the ground lest they be flipped like fleas into the sky. More groans and booms shook the world. Dust and water vapor boiled into a swirling brown mist.

Drenched in mud, Amenstar huddled like a whipped dog and prayed: “Dark Destroyer, take me away! Blind me, Orus of the Thousand Eyes, so I never see such a sight again!”

As if drawing close to witness their destruction, the overcast sky lowered until Amenstar feared to stand and attract lightning. Thick air choked her as well as fear. Cracking and crackling now shook the sky while everywhere rocks broke, sheared, and tumbled, pulverized. Still the shaking hummed through Star’s body until she felt her bones would shiver into jelly.

Above the noise, Tafir shouted, “L-look at the c-clouds!”

Hunkered like bugs, spectators craned their necks to see the sky. The blanketing overcast had split in a thousand places. Scattered clouds coalesced into deeper black patches. Far off in a more peaceful world, the sun was setting, and shafts of brilliant yellow slanted across the landscape through a thousand holes in the sky. Amenstar caught her breath at the phenomenon. It was like a hailstorm of sunbeams.

Tafir pointed out one massive cloud directly overhead, a roiling gray-black anvil tinged red by the setting sun.

“It’s a genie,” the princess blurted. “Genie smoke!”

“Spirits of the Sands,” Pallaton shouted as he scrambled to his knees. “It must be Almighty Calim himself. Run! Get off the hilltop!”

Terrified, blinded by dust and mist, Amenstar only saw dimly as the chief vizar and his acolytes scooted to their knees, raised their arms, and sent up prayers to the greatest genie of legend. Their escort of guards were less certain it was time to pray. Some stood still and gaped while most ran pell-mell away from the riverbank.

Pallaton grabbed Amenstar by both shoulders and jammed her slack body to his breast. Slapping Gheqet and Tafir before him, the prince took three loping strides and quit the hilltop. Rocks and sand jigged underfoot as he struck the downslope and lost his footing. Star tumbled end for end, down to where their horses had been killed by rolling rocks.

They heard what happened later from spectators ranged along the rocky slopes. Seconds after Pallaton and the Cursrahns vaulted from the hilltop, from the deepest part of the roiling thunderhead flashed lightning so bright people recoiled as if struck in the face. A sizzling bolt scorched the air and struck the hilltop square on the chief vizar and his pilfered scepter. Watchers grunted in sympathy as the priest and his acolytes exploded into charred gobbets of flesh that rained far out over the rocks and splashed into the churning river.

There came a pause while the world froze, and waited.

Thunder, an unimaginable crash that rattled teeth and jarred bones, slammed the land as if to punish it. Anyone who’d stayed half-risen was knocked flat by the explosion, and everyone feared they’d been permanently deafened. In a jumble of rocks and sand and horseflesh, Samir Pallaton craned to look up the hill. His mouth hung open, his pallor ghastly white.

Above a high buzzing whine, Amenstar heard a squeak, and realized it was Tafir shouting at the top of his lungs: “I think that scepter was real!”

“I think Calim took it back,” replied Gheqet. “It’s—oh, no!” Crawling to his frie

nds, the architect’s apprentice tried to drag both Star and Tafir to their feet. “Look there—the ridge cracked—the river turns!”

Struggling to their feet, supporting one another, the three friends gazed at the River Agis. It boiled and churned in its rocky bed, a torrent of hissing water, mud, and sand. Along the Agis’s old course, the watchers realized, the shattered hills had slumped into the riverbed and blocked it for half a mile or more. Tiny trickles seeped amidst the jumbled rocks, but the barrier dammed the water completely. Denied its usual route, the mighty Agis backed up. Water seethed and trembled in whirlpools and maelstroms, then began to spurt along the northern ridge of the river, where its stony restraint had cracked.

“There it goes!” hollered Gheqet.

Unconcerned with its destination, the River Agis rushed and pushed against the cracked northern face, and broke it. As the ridge shattered, Pallaton’s newly dug ditch beckoned. Astonished slaves clung to the walls of their tiny valley and watched the River Agis gush into their earthworks and fill it, turning a barren gash into a true living canal. Water lurched and slopped and boomed northward, scouring the canal and carving a new riverbed amidst the constricting hills. As Pallaton’s engineers had predicted, the river had turned, found lower ground, rushed in, and now flooded off out of sight.

Northward, many miles, the river would once again hook west, inevitably driving for the sea.

“Great Calim,” Gheqet whispered, “help Cursrah in her hour of need.…”

“It can’t be,” Amenstar gasped, and her breath turned into a sob. Tears burned her cheeks.

Samir Pallaton had predicted accurately. Not a drop of the Agis’s life-giving water would ever reach Cursrah again. With the riverbed forever blocked, the famous aqueduct five miles west would run bone dry within hours.

For the first time in her life, Amenstar wept for her homeland. Her parents had spoken the truth. Without water, Cursrah would soon be swallowed by the desert.

11

The Year of the Gauntlet

Haunted by visions of impending death, once again Amber stumbled and blundered across the burning desert tethered by the wrists to a cruel and uncaring ogre. Sun scorched Amber’s face, beat on her head and back, and soaked through her filthy, torn clothing until she felt her blood would boil in her veins. Her legs were clumsy with fatigue and hunger, her mind dizzy from lack of water and sleep. Her face hurt the worst, still seared and blistered from the White Flame’s torture. She was chilled by their ultimate fate waiting at the band’s destination, and she prayed fervently to Ilmater, goddess of suffering and martyrdom.

Only Reiver’s and Hakiim’s frantic pleading had saved Amber’s face and their lives. Yelling at the top of their lungs, the thief and rug merchant’s son had insisted that untold wealth and riches awaited them in the ruins of Cursrah and repeatedly shouted that only Amber knew where these riches lay, having been befriended by the palace’s undead guardian. Promised gold and jewels, the nomads had plucked Amber from the fire, and the White Flame had hesitated to execute her. The Flame lived for vengeance, but her followers lusted for wealth, and they’d keep Amber alive until it was found. Nomads had slapped mutton fat on Amber’s face to quiet the burns, and they fed the prisoners meager rations, not out of kindness, but out of greed. That a magic-wielding mummy guarded the treasure was a fact everyone conveniently ignored.

The bandits broke camp and trekked into the desert just as the sun rose. Stumbling across sand and gravel, Amber listened to her captors talk, partly to learn about her enemy and partly to detract from her own suffering. The bandits were a mixed lot of oddballs with little in common, Amber learned, and she desperately hoped to exploit that flaw and somehow escape.

The White Flame constantly muttered to herself or to imaginary enemies about gaining power. The crazed leader hoped to find magicks or scrolls to aid her campaign for vengeance. A few tall bandits were Tuigan barbarians from the hills, who lusted to loot a desert city buried since ancient times. In olden days, they assured one another, nobles were buried with treasure to buy comfort and position in the next life. Robbing one tomb would yield enough booty to buy luxury in this life, and the devil take the next. Some of the raiders were dwarves of the Axemarch Stone Clan, who considered tomb raiding the most heinous of crimes, and grumbled in guttural tones. They hoped to find magical tools or loose gems, or crowns and armor, but not in coffins. The majority of nomads were southerners from the Land of the Lions, a somber lot who talked little. Amber glimpsed a face now and then, with tattooed dots and lines on chin and jaw. A few bandits lagged far behind and never spoke or shifted their veils, so only yellow or mismatched eyes showed. They might be half-orcs, but from their painful shambling gait Amber guessed they were mongrelmen from the Marching Mountains, bastard offspring sporting the worst features of talking races and animals.

Thirty-odd bandits, Amber guessed, though their numbers were never clear because the band sprawled in clumps over a mile or more. Amber glimpsed the raiders mostly over her shoulder, or at rest stops in three days of marching, for the White Flame and her bodyguards stuck to the center, with the ogres and captives in the van.

The breed-ogres Amber understood not at all. Enigmatic creatures, they might be freebooters or else outcasts from their pure-blood tribe. Why they traveled with a human-led band or what they hoped to gain, Amber couldn’t guess. So far they’d gathered only three careless young Memnonites, a few coins and gems, and the moonstone tiara. The biggest giant, the slow-moving brother, had picked up the tiara when the White Flame discarded it and no one else, for superstition, would touch it. The ogre had slid it onto its left arm below the elbow, and no one contested its ownership. In the same way, the big brother carried Hakiim’s scimitar, Amber’s capture noose, and their rucksacks. The monsters took precious little care of their slaves, barely feeding them and administering kicks and jabs rather than water. Dragged behind the magic-plying, smarter brother, Amber was convinced that, upon reaching dead Cursrah the unneeded Hakiim and Reiver would be killed. Their scalps would be strung onto the ogres’ fearsome spears and their bodies strung onto spits and roasted. Amber might be kept alive until she pointed out the spiraling tunnels to the palace cellars. The ogres showed jagged teeth like sharks, and Amber shuddered to think of fangs tearing her charred flesh from her bones. She felt partly crisped already, for heat made the mutton fat run from her face into her collar, and every wink of sunlight was like sandpaper brushing her burns.

Amber could imagine no escape. Hakiim and Reiver were also exhausted and helpless. The rawhide binding their wrists was old and rotten but tough enough in multiple strands. When it broke the ogres simply re-tied it in a hash of knots. Even freed, the half-dead humans could never outrun the indefatigable and long-legged ogres or the other bandits spread across the dunes. No, Amber thought, they were helpless and alone, stumbling across rocks hot enough to crackle. Or perhaps not so alone.…

The magnificent hunter genie Memnon, claimed some travelers, lay bound in the soil, and when angry at desert interlopers manifested Memnon’s Crackle, a seething vortex of sand. Further, said others, Memnon could be invoked with a stonetell spell so his face appeared in solid rock and he spoke. Memnon was always that close. If so, then even closer was another genie, for the breeze that cooled Amber’s parched face was said to be the very breath of—

“Great Calim, Lord of Genies, Qysar of Calimshan, hear my prayer,” Amber whispered as she marched. She was uncertain if genies attended prayers, as gods were wont to do, but she’d try anyway. “These thieves seek to loot your city, sacred Cursrah built by your own mind and hands. They’d violate Calim’s Cradle and the famous college, created to honor your memory, to sing your achievements, to boast to the world of your greatness. If these people reach the valley, they’ll smash any vestiges of wonder and pilfer the gold and silver given in your name. Not so me and my friends, as you saw. We found your great city and yes, picked up odd coins, but mainly we wished to see Cursrah’s secrets, to plum

b the depths of your greatness. Deep underground dwells a mummy, a living relic of your greatest hours, and I would help that poor mummy, whoever he may be.…”

Mishmashing every prayer and hymn she knew, Amber babbled to an ancient, unseen genie whose only hint of existence was a breeze against her cheek—but who’d also blasted with lightning a vizar who’d presumed to usurp Calim’s power.

Talking, Amber surprised herself. She really didn’t want to loot Cursrah, she realized, but she truly wanted to learn more about the mummy; why it stalked the dark corridors, why it touched her mind and sought rapport, why it pleaded with Amber for help, if that was truly its message. What could the undead want from the living? How could Amber help an animated corpse whose soul yet lingered and languished in awful, aching loneliness? The daughter of pirates couldn’t guess, but if Great Calim let her survive long enough she’d find out, she silently vowed, or die trying.

Stumbling, falling repeatedly then dragged, Amber prayed until her dry throat seized up, choked by dust, and she could only move her lips in silence. Agonized by thirst and exhaustion, shocked by the fierce burns weeping from her cheeks, nose, and forehead, the young woman would have cried in despair if she’d had any tears left. Her useless prayers were whipped from her lips and dissipated by the rising wind.

Rising wind?

Forcing open gummy eyes, Amber turned her face and was peppered with sand. Dust billowed from nearby dunes, swirled in dust devils around her aching feet, and fetched in folds of her headscarf and tunic. Some of the bandits were already obscured by curtains of sand that lifted and died and redoubled. The White Flame flicked a bony hand, and a bodyguard raised a curled ram’s horn and blew a ratcheting wail that brought outwalkers closer lest they be separated in a sandstorm.

To be separated from this crew would have suited Amber. True, three puny humans stood little hope of fighting three breed-ogres; still, any change favored their chances. Squinting against sand and the darkening sky, Amber wondered if Calim indeed aided them. She rattled more prayers and praise through gritty lips.

Dangerous Games

Dangerous Games Mortal Consequences

Mortal Consequences Bold as Brass

Bold as Brass Star of Cursrah

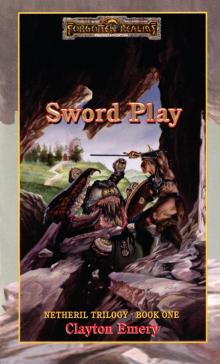

Star of Cursrah Sword Play

Sword Play